Discover the Microclimates in Your Garden

While in college, one of my design classes spent a few days in Boxley Valley along the Buffalo National River in Arkansas to analyze this historic site for a project. Emerging from our tents in the cool morning, desperate for a hot cup of coffee, our instructor pointed out the other tent in the campground. That tent was covered with frost while ours, sited under evergreen trees, were not. The evergreen canopy kept our tents a few degrees warmer and protected from frost.

While studying landscape architecture I heard many lectures on microclimates: south slopes are warmer than north slopes, cold air settles into valleys, morning sun is less harsh than afternoon sun. But seeing and feeling the difference in microclimates within that small campground was a vivid and memorable lesson-a few feet in one site can make a difference.

The moment you realize that your property is made up of many little microclimates you instantly become a better gardener. There is a reason why the azalea planted where it receives irrigation and afternoon shade is thriving in your neighbor’s yard, while yours, under the same cluster of pines but receiving afternoon sun and little water, is stressed. A few feet in a garden can make a life or death difference to a plant, which is why gardeners move plants that do not seem to be happy.

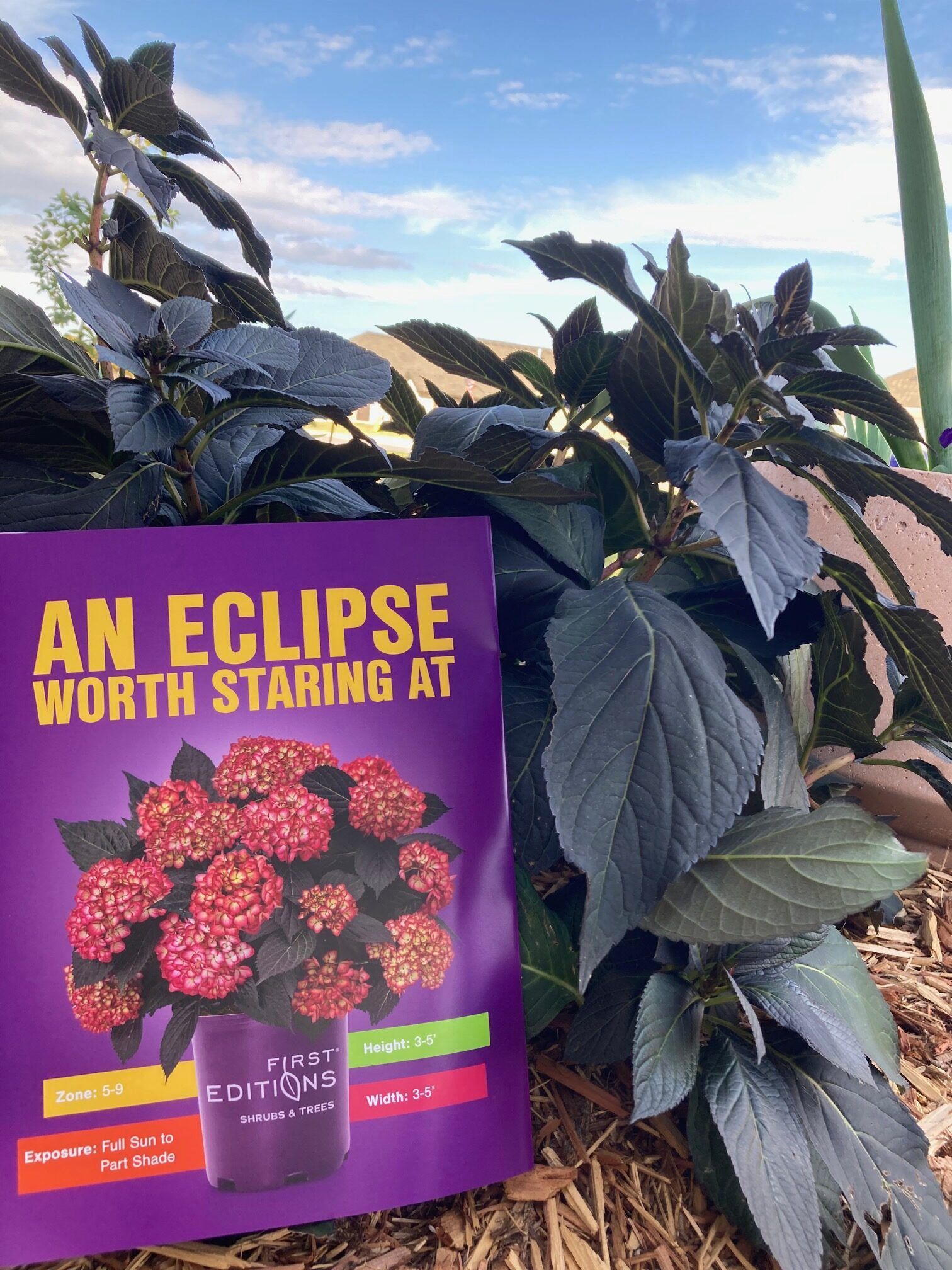

Our property is a high point for our neighborhood, so I hesitate before bringing moisture-loving plants into my garden. Moisture loving trees are simply not an option for this site. I refuse to garden without hydrangeas and hostas, which love water and are favorites of the browsing deer. So these are clustered together under an old pecan tree that I revere. When I ration water during a drought, this area is the last to be denied our precious well water.

A few feet from the pampered hydrangeas is a red maple, which seems to claim all available sunlight and moisture from the raised bed around its trunk. Several plants have perished in that extreme environment; the proven survivors for such dark, dry, deciduous shade are spring bulbs, epimediums and columbine.

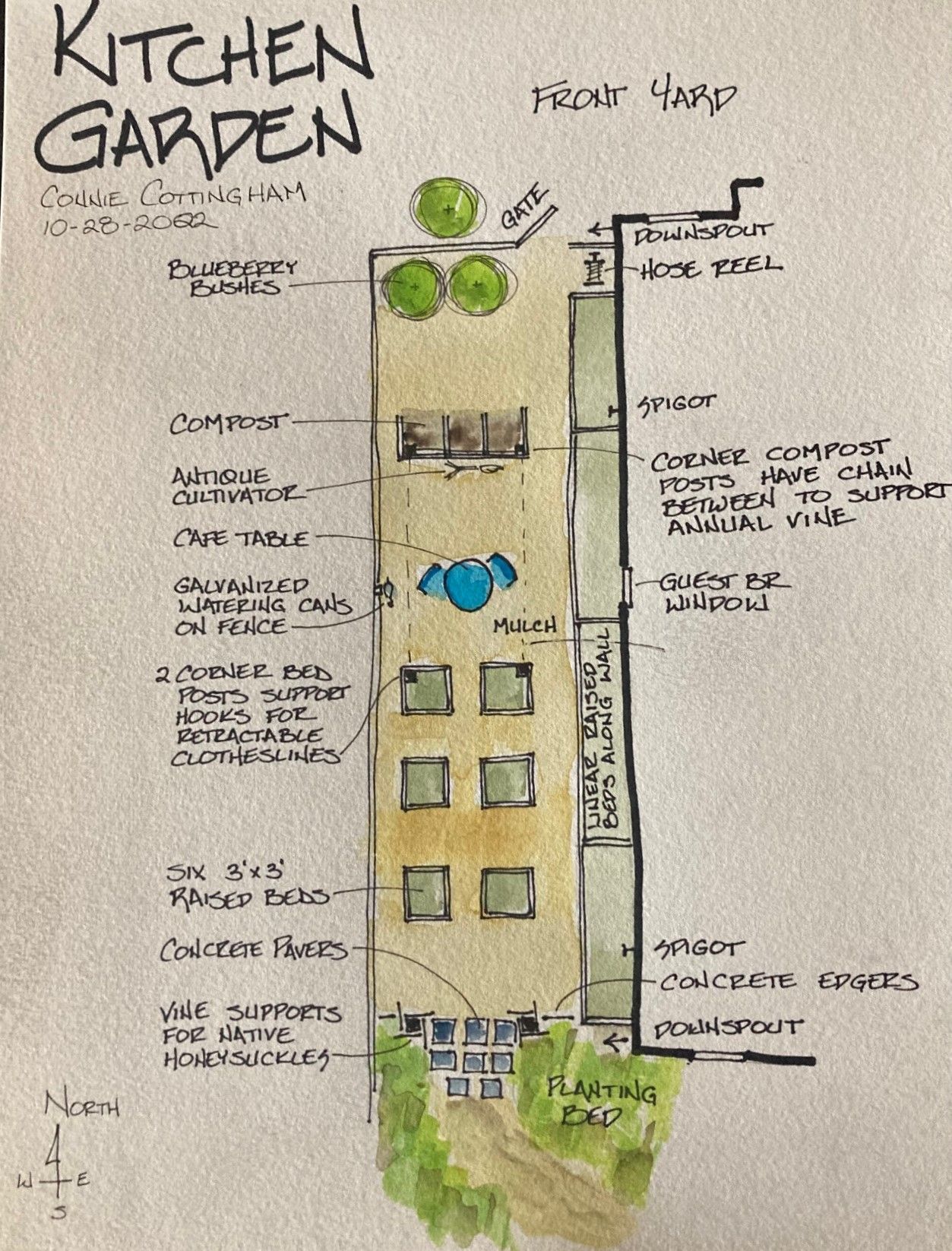

OK, so let’s take a quick walk around your home and look at typical microclimates. The east side receives the morning sun and afternoon shade. The south side gets sun for most of the day. The west side stays shaded in the morning, then gets brutal afternoon sun. The north side stays pretty shaded, but can get afternoon sun in the hottest part of the year. Sounds simple, but few of us live in a rectangle in the middle of a field. The many angles and height of the house, trees, fences, pavement, moisture, soil composition, wind, and more affect your plants. A windy site may dry out foliage. A sheltered area may allow you to grow a plant rated for one zone south (at least for a few winters). Near my home hydrangeas are placed near the downspouts on the east side-sites that offer both afternoon shade and moisture. Rosemary thrives in the brutal area under the south eaves that gets plenty of sun and limited rain.

A plant that can take full sun in Michigan may not be able to handle full sun here in the Southeast. For us ‘part shade’ means morning sun and afternoon shade, while any location that receives three to four hours of afternoon sun, even if it is in the shade until 2:00 in the afternoon, counts as a ‘full sun’ site when selecting plants.

The best way to know your garden is to spend time in it throughout the year, learning where the water flows, where the sun shines at different times of the day and year, and which plants seem happy. To further complicate things, a garden is constantly changing, with trees growing and dying, changing sun angles and more. A few years ago drought tolerant plants were all anyone wanted to talk about here. But weather is always changing. Plants that are suited to a site are the healthiest and the healthiest plants will be best able to survive any weather extreme.

Yes, you can learn about gardening from a book, but the best way to know your garden is to garden in it. You will kill some plants (every gardener does) and move others, you will make mistakes, but you will also find out what works well for you and build on successes. Being aware of the microclimates within your garden will help you be a more successful gardener.

(adapted from an article first published in Lee Magazine, May 2008)

Love Notes From The Garden

Subscribe to brief, free, weekly emails containing a garden tip, introducing you to a garden plant or reminding you of a garden task.

Love Notes Email Submission

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.

All Rights Reserved | Garden Travel Experiences

Website by Madison Web Design, A City Web Design Company